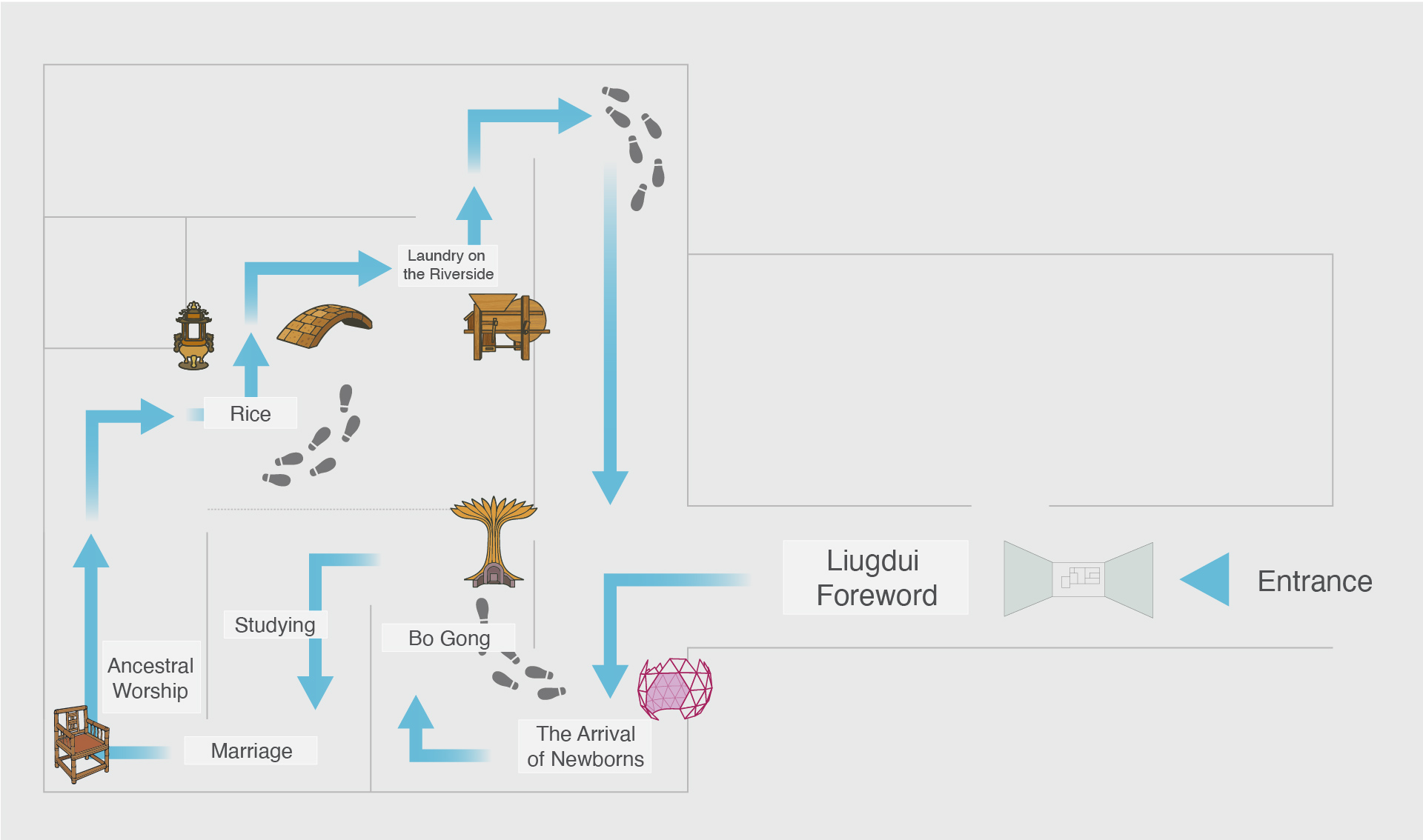

Liugdui Foreword

English

Hakka

Click the button above to play the audio tour

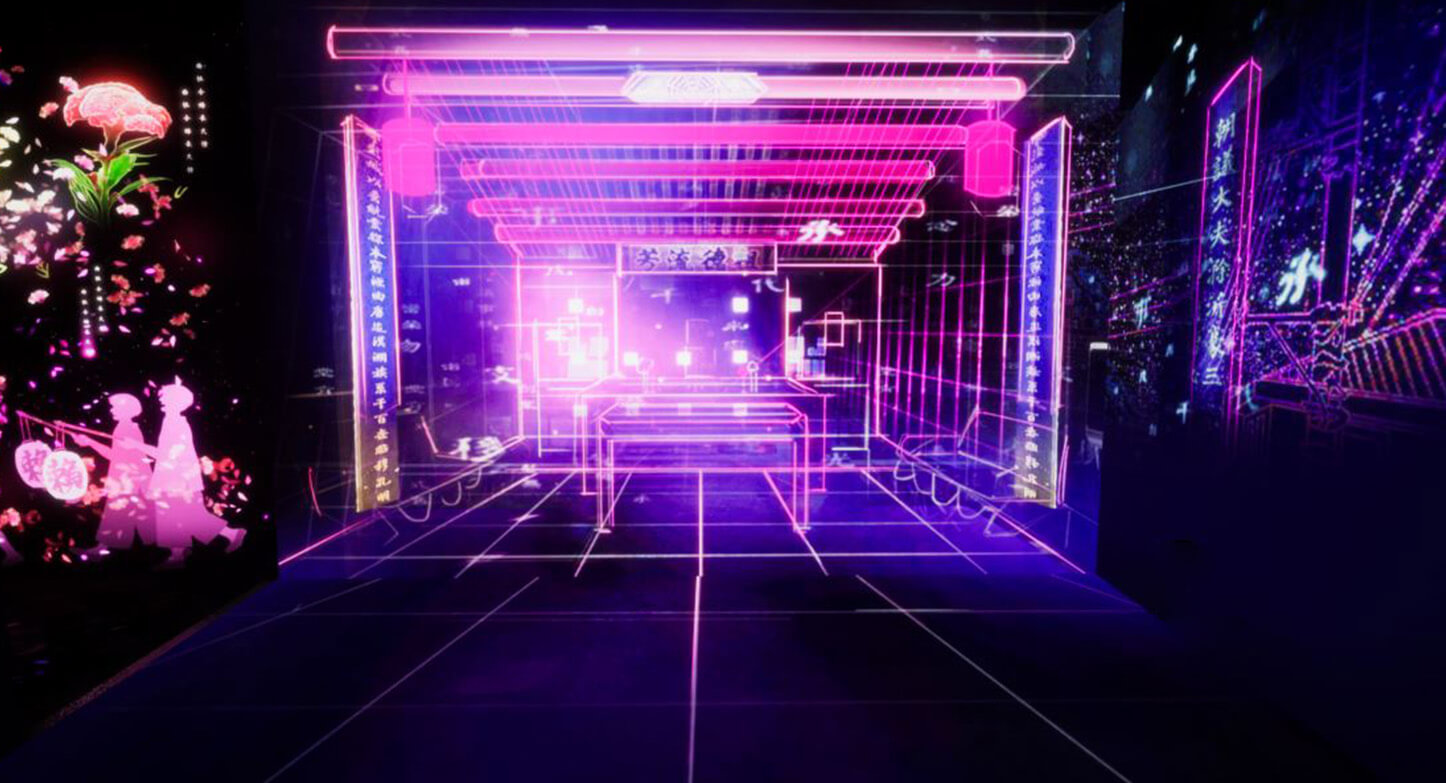

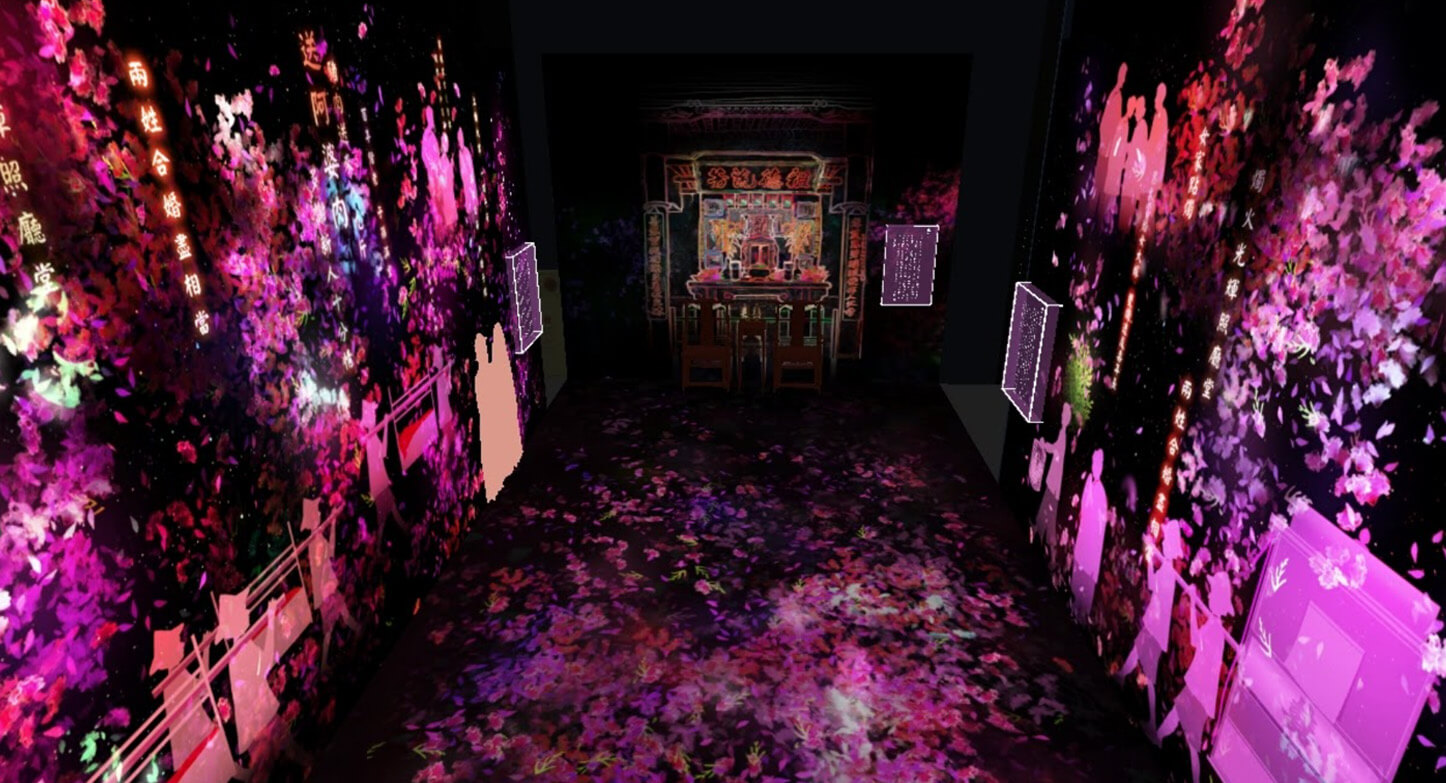

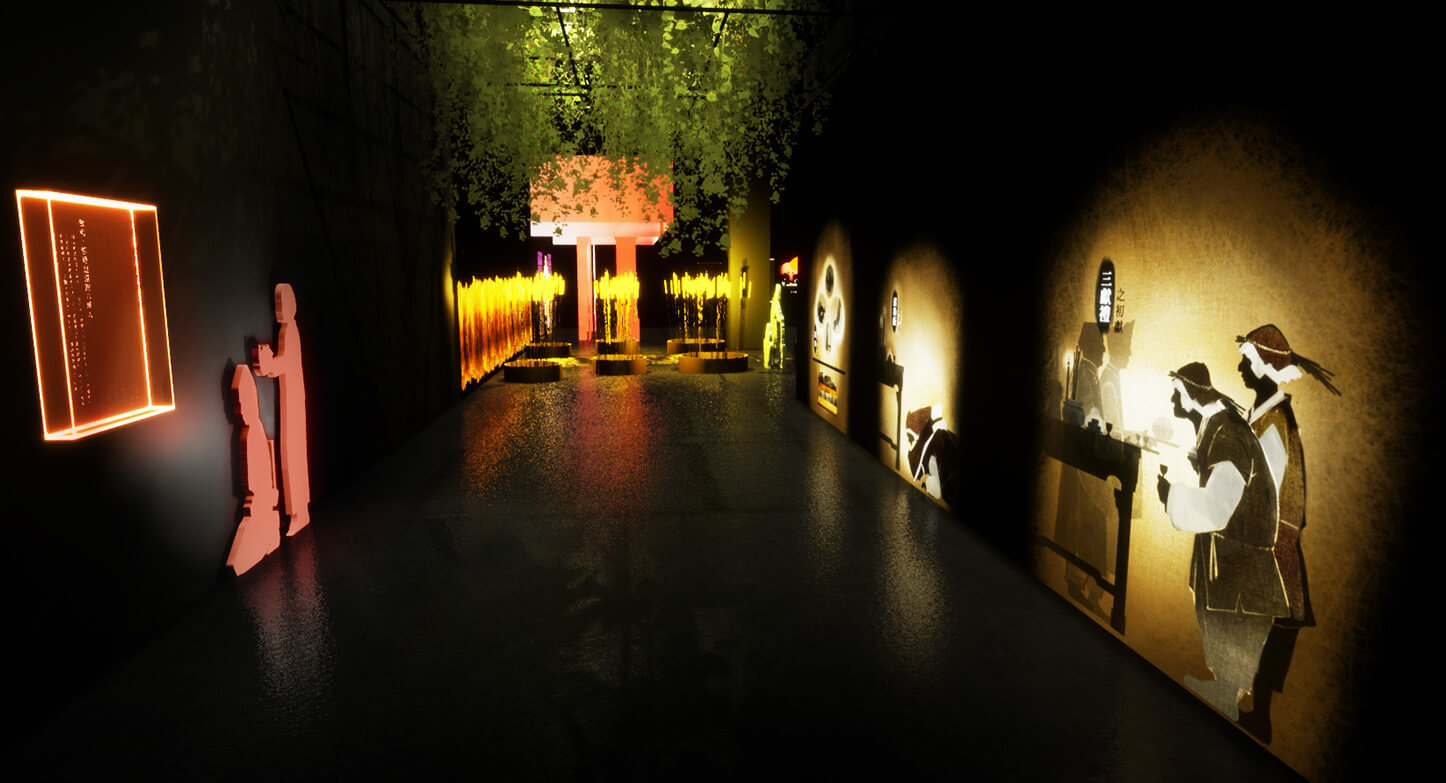

The warm and sunny Pingtung Plain is surrounded by the Laonong, Ailiao, Donggang and Linbian Rivers. The Laonong and Nanzhxian Rivers converge to form the Gaoping River, formerly known as the Lower Tamsui River. Prior to the Han Chinese settlement in Taiwan in the 17th century, the Pingtung Plain was inhabited by the Feng-Shan eight tribes of Pingpu indigenous people. After a series of historical developments, Taiwanese indigenous people, Pingpu tribes, Hakka and Holo people came to coexist on the Pingtung Plain. The Hakka people of Liudui settled along the spring belt, on the edge of an alluvial fan formed by the Laonong, Ailiao, Donggang and Linbian Rivers. These Hakka immigrants from China were drawn by temperate climate, ample water source, and Shuang Dong Zao Dao (literally, double-winter early season rice), which means early season rice that can be harvested in the third and fourth months of the lunar calendar. When the Zhu Yigui Rebellion erupted in the 60th year of Kangxi’s reign (1721), the Hakka settlement had already expanded to 13 villages and 64 hamlets. The Hakka settlers had formed the Seven Camps (Qi Ying) to defend their villages during the Zhu Yigui Rebellion. Then in response to the Lin Shuangwen Rebellion in the 51st year of Qianlong’s reign (1786), troops were dispatched under the banner of Liudui, as a region-based, mutual defense group consisted of Qiandui, Houdui, Zuodui, Youdui, Zhongdui, and Xianfengdui. This form of settlement development has been passed down to this day. Over the past 300 years, the Hakka people of Liudui have preserved their native tongue and distinct cultural characteristics, through the changes of the times and political regimes. Meanwhile, Liudui has evolved from the name of a mutual defense group, that aimed to safeguard the homeland, to a byword for Hakka cultural community.